Rejections, I’ve had a few

I had seven rejections for my first novel and each was as painful as a graze. Random House took it on in the end, probably as a favour to my editor/agent, and then held it back from publishing for eighteen months When it was finally published, it was shortlisted for the Miles Franklin. That year a crime writer won. I was also nominated for the Prime Minister’s Award. At the announcement for that prize, we stood around in a big room with slides of our books on the walls, faded in the sunlight (no fancy dinner you were too nervous to eat). I remember looking at Julia Gillard as she mingled and our eyes met and an electric shock rippled through me, I thought it was a sign. It wasn’t a sign; it was a glance. She was just electric.

I won neither but getting shortlisted for them was like winning without the money. It’s a wild little lottery.

Some of the early rejections were biting. One comment said that ‘Emmett’ was attenuated, and I had to look that up and found: (adulterated, impaired, or impoverished). Oh my God, I thought, my vocabulary needs extending to handle the critiques. Of course, I couldn’t see it as impoverished (though my childhood was) but who knows what others think? The editors have the power, and they use it. They are not your friends, they’re like record producers looking for hits not classics.

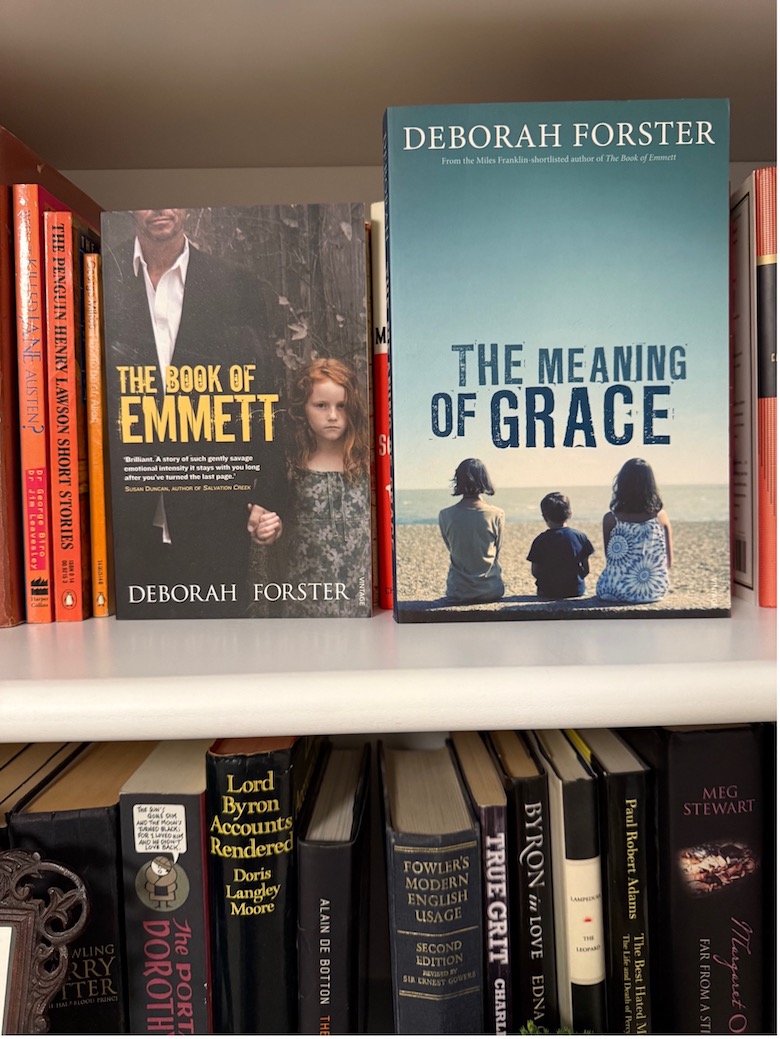

‘The Book of Emmett’ was the result of the first years of my life, so I can’t be impartial, I am my own umpire there. The book was about being in a hostile place and surviving a strange person and it was about family and deep love, about my family fictionalised, which involves ironing out and evening up. It was about understanding something bigger than me and if nothing else, it gave me that. The book is largely true, you couldn’t make my Dad up, and I have no problems with that, I knew I’d write the story one day, it got me through. You write what you know, unless you’re going for spy, crime, romance, or any other fantasy.

My father was a very unusual man; terrifying, violent, impossible, occasionally insightful, kind and even funny, but he was mercurial and demanding and through all that I possibly loved him, not consistently but well enough.

It’s the stuff of many books, though each of them particular to place and personality. ‘The Man Who Loved Children’ by Christina Stead gave me the strength to write it and it’s why the main character is named Louisa.

My son Chris saw a woman reading ‘Emmett’ on the tram after it just came out. He watched her smile as she read it. He was thrilled and rang me, and I wept to think someone had even bought it.

The second book ‘The Meaning of Grace’ was not so successful but it was voted most popular novel in Western Australia, for which I will always love the sandgropers. I had a two book deal with RH on the first book, so ‘Grace’ was going to be published regardless. ‘Emmett’ was the father book and ‘Grace’ the mother book.

Mum was steady, hard-working, but she couldn’t rescue us from dad. She toughed it out with her quiet inward-looking style. That was how she survived. I knew even from a young age,that I had to negotiate my relationship with my inexplicable father on my own. I did it by hiding away in books and trying to be good. He liked that I read, so it softened the corners of some things. ’Grace’ has plenty of ‘Emmett’ in it but it’s set when he’s older and less savage. Also ‘Grace’ focused more on women and unless you’re Alice Munro, they don’t do so well. Mum read an early draft of ‘Emmett’ and thought it was a bit like ‘A Fortunate Life’ by Bert Facey which made me sad. She died in the first year they held it.

Pretty soon after ‘Emmett’ came out, I realised that I’d had my moment, and it hadn’t lasted long at all, about as long as an afternoon tea with the Mad Hatter in the scheme of things. I was fifty two when ‘Emmett’ came out. Other things were going on; three children, a husband who worked constantly, a column for ‘The Age’, dogs, cats and I suppose I forgot to keep going but there was something else.

I have a robust strain of depression that arrives fairly often, and another bout was usually on its way toward me. It took me out of the game for years. I did write some short stories and one day I got the courage to ring the editor I’d hired for ‘Emmett’. I got lost driving to Elwood to show them to her. It did not go well. She said the stories were as down as I was (here I was thinking I was hiding it). So, I paid for the coffee and her time and got lost driving home again and chucked the stories in the drawer and forgot them.

Then as it is with this illness, when it lifts, you see the sky and you start to believe. I read them, did what the editor told me to do (not be down) and fooled around with them for years. In that time, I’ve been in hospital several times. So, it’s been about fifteen years since ‘Emmett’ was published and though I think the stories stand up, I’ve missed the boat. These are the stories of my life, not my parent’s lives, mine. They mean something to me, and I can’t get them published. The industry has changed into something else.

In the last batch of rejections, the first person to read them kept them for nearly a year and then said, ‘I cannot publish these stories. They are just too sad.’ I’m sure you’re getting the picture. Editors are individuals, there’s a lot of personalities in reading and even if they like something, it has to make money.

The second reader was at a smaller publisher. She was kind and made great suggestions which I did immediately, and I’m grateful to her. The third held the stories for a year and finally at midnight on a Friday night, ding went the phone message, and foolish me, I checked it. A friend had prodded him. This editor said he liked them but couldn’t publish them. After that, I was awake till 3am. I can’t sleep much anyway, but each rejection is like a pillow on your face. At least he had the manners to be human and considered and I thank him. He said this age doesn’t have much time for unassuming people (which my people are), that ‘we are in an era reserved for the brash’. He thought that because everything these days is about the book generating its own heat, that a collection of short stories was basically almost impossible. He said the stories were like something by Graham Swift. Wonder if he gets published. I’m sure I’d like his stuff.